Molly Moffett was shocked when her bill arrived in the mail. After months of screenings and physical therapy required by insurance for a herniated disc, she finally got in to a specialist for a steroid injection.

Moffett’s doctor was in her insurance network. But unknown to her, the facility where the procedure was scheduled wasn’t. That cost her an extra $3,000.

“It took several months of me being in a lot of pain until I could get what I needed,” Moffett said. “I think everyone struggles with these things. I always tell people, just ask as many questions as possible.”

Moffett is no ordinary health care consumer. As a project coordinator at the Community Health Council of Wyandotte County, she spends most of her time helping people get access to insurance and understand how to use it.

“I think the fact that our health care system is so complicated creates unnecessary barriers for a lot of people, whether you’re low income or high income,” Moffett said. “It’s frustrating because it feels like people are giving you different answers and you have to go through all of these different steps.”

With more companies offering consumer-directed health plans and provider networks referring to patients as consumers, the onus increasingly falls on patients to advocate for themselves. But it’s difficult to be a savvy consumer in the face of arcane health care systems and little to no information necessary to compare outcomes and costs.

Dizzying information

Trying to compare costs of procedures at various hospitals demonstrates that even what are billed as transparency efforts fail to present a clear picture.

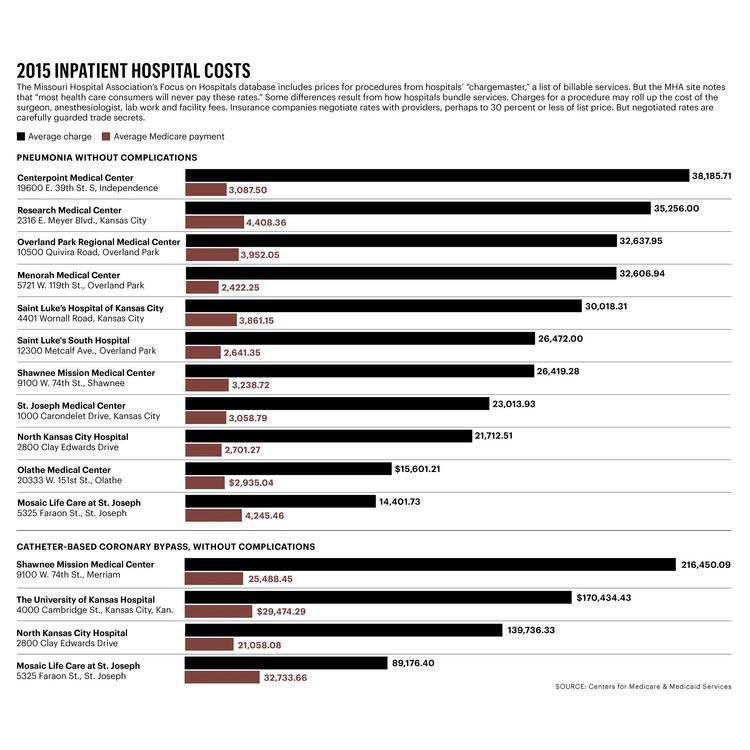

The Missouri Hospital Association’s Focus on Hospitals database includes 2016-2017 prices for procedures from hospitals’ “chargemaster,” a list of billable services. The database shows that the median charge for heart catheterization for a condition other than a heart attack, without complications, is $25,831 at Mosaic Life Care in St. Joseph and $51,547 at Shawnee Mission Medical Center. But the MHA site notes that “most health care consumers will never pay these rates.”

Now, try to compare that with information from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. The 2015 list price for a catheter-based coronary bypass ranges from $89,000 at Mosaic to more than $216,000 at Shawnee Mission Medical Center.

The amount Medicare pays for the procedure is more consistent, ranging from $21,000 to $32,000.

Some differences result from how hospitals bundle services. Charges for a procedure may roll up the cost of the surgeon, anesthesiologist, lab work and facility fees.

Insurance companies negotiate rates with providers, perhaps to 30 percent or less of list price. But negotiated rates are carefully guarded trade secrets.

Mash it together, and patients are left with price information that “few mortals can decipher,” said John Leifer, a Leawood-based health care consultant.

“We have been talking about price and quality transparency for 25 years, at least,” Leifer said. “The prices that are quoted in health care are so far from reality. There are so many impediments to getting that true pricing. It’s a Herculean task for any company to try and overcome this barrier.”

Even with more information, it would be tough for consumers to make important decisions. For example, Leifer said, if your father is going in for heart surgery and you have a choice between a hospital that charges $75,000 with a 1 percent mortality rate and another that charges $40,000 with a 3 percent mortality rate, what do you do?

“We need really good data, and we probably need to have it interpreted,” he said. “Consumers are neither discerning nor demanding when it comes to making smart health care purchases.”

Attacking the problem

Companies are working to help get more actionable data to companies and consumers.

Matt Condon’s Bardavon Health Innovations is working to gather information for all facets of workers’ compensation care. Spending on musculoskeletal injuries in the U.S. is higher than for cancer, he said, totaling about $35 billion in medical costs and an additional $35 billion in indemnity.

“Employers actually want a better provider who’s getting a better outcome. They’re financially incented to do so,” Condon said. “Knowing which doctors are most likely to heal patients is the holy grail we’re trying to get to.”

Although workers’ compensation care is a unique area, Condon said he hopes the idea of actionable data driving decisions can be expanded to the larger health care space.

Kansas City-based Health Outcomes Sciences Inc. uses predictive analytics to provide risk models for individual patients before certain procedures. This information could allow low-risk heart patients to avoid wasting time and money on unnecessary treatments, while seeing that high-risk patients are treated appropriately.

Kansas City startup iShare Medical LLC helps patients view and share their health records securely.

Condon said startups are best positioned to disrupt the status quo, where doctors and patients alike have spent decades battling the same problems of misaligned incentives, lack of transparency and inadequate information.

“Our system has historically tried to do the same things,” he said. “We’ve got to be irreverent about almost every single aspect of the status quo.”

Learning to navigate

Navigators and advisers can help patients figure out their needs and even do some of the legwork of getting care.

Moffett helps patients navigate insurance plans offered through Affordable Care Act exchanges. That includes helping people — many of whom are getting insurance for the first time — understand jargon, network limitations and deductibles.

“I think insurance companies are trying to do a better job, but it really comes down to whether patients are asking the right questions,” she said. “I have seen people afraid to use their insurance even though they know they need it. The process to get there can be disheartening.”

HCA Midwest, the area’s largest hospital system, began putting nurse navigators in its hospitals three years ago to help cancer patients get information on procedures and schedule doctor appointments. It has expanded the program to cardiovascular, gastrointestinal and perinatal patients.

“It’s taking some of the pressure off the physicians and their office staff,” said Brent Pike, regional access director. “I think that’s helped patients a lot because they know they have someone they can call.”

Dr. Darryl Nelson, HCA Midwest’s chief medical officer, is working with the system’s physicians to focus on patients’ needs instead of what works best for the care provider.

He became attuned to the problem some years ago at his family medicine practice in Lee’s Summit.

“It was prompted by a walk by the front desk, where I saw my poor dear staff person just red in the face and distraught,” Nelson said. “She was trying to explain to a patient it was going to be weeks before they could be seen.”

Originally published in the Kansas City Business Journal, March 9, 2018